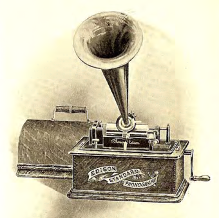

Edison Standard Phonograph

Object Biography: the “Edison Standard Phonograph”

Introduction “The Miracle of the 19th Century”, “The Talking Wonder”, that can enunciate and pronounce speech “in every known language”, this is how the predecessor of the object was introduced in an advertisement to the public in 1878.

The technical device on which this object biography is focused is the EDISON STANDARD PHONOGRAPH. The Edison Standard phonograph was invented by Thomas A. Edison in the late 1800s. This object allows both recording and playing back recorded sound.

While we will see that Edison’s idea about the use of the phonograph was quite specific at the beginning, the full use of the Edison Standard phonograph’s recording and playback functions can be enjoyed (please refer to footnote for youtube link) in full based on an example from the Thomas Edison National Historic Park.

Background

Thomas Edison’s invention of the phonograph dates back to the last quarter of the 19th century, exactly 1877, being a result of two further inventions: the telegraph and the telephone. On 6 December 1877 Thomas Edison was in his famous laboratory at Menlo Park, New Jersey, only a few kilometers away from Manhattan. This Menlo Park laboratory became later on so well-known for his famous inhabitant, not only in respect of what will happen there in relation to the phonograph, but also with respect to what he demonstrated two years later, with regard to the development of the commercially usable light bulb, that it was decided in 1954 to change the entire name of the locality to Edison, in honor of the great inventor, Thomas Alva Edison. On that day in December 1877, after having been working on his invention of the phonograph for many months, there was the day where he finished his series of experiments on his apparatus. Edison shouted the poem “Mary had a little lamb” into the mouthpiece of the device. A stylus scratched the vibrations of the nursery rhyme directly into a rotating cylinder covered with tin foil. Only instants later, Edison’s exact rendition of the first lines of the “Mary had a little lamb”-poem was played back to him . Thomas Edison exactly said the following words which he recorded on his device: “The first words I spoke in the original phonograph. A little piece of practical poetry. Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snow. And everywhere that Mary went, the lamb was sure to go.” Then he listened to what he had said (and recorded) seconds before. This wording can still be listened to nowadays (from digital copies of the initial recording on the tin-plated cylinder). Listeners will experience the scratchy sound of the first Edison phonograph, which is due to the metallic sound produced on the tin support. How had Edison come up with the idea to build a phonograph? The idea of the phonograph came to Edison in that year 1877, when he wanted to further refine the telegraph which he had already technically improved in 1868 (which brought him his first patent). He now wanted to increase the speed of the message transmission, which was still a problem as the message could pass only as quickly as the telegraphist would write it on the support. Edison’s idea was to first record the Morse code message on a paper strip by indenting it thereon: then, the paper strip would be passed under a tracing point were depending on the indentation on the strip the circuit of the telegraph would open or close. The paper strip with all the message already on it could be passed quicklier than the telegraphist would be able to typewrite the message while passing it under the tracing point. Edison tried this procedure and realized the noise was a sound which was like “a musical, rhythmic sound resembling that of human talk heard indistinctly.” The noise showed him that this also allowed the amplification of telephonic voice signals. He attached the embossing point to a telephone diaphragm and created an indented paper record of his voice, he described this experiment in his notebook saying “[T]here is no doubt that I shall be able to store up and reproduce automatically at any future time the human voice perfectly”. Based on this experiment, Edison’s phonograph was born, finally with a long, narrow strip which this time wasn’t of paper anymore, but which was a thin tin foil strip which was fixed around a cylinder. By putting the cylinder in motion, with the needle put on it (with which the signal was engraved in the tin foil), it became possible to record and reproduce sound .

THE OBJECT

This birth of the first phonograph made by Edison was followed by various improvements of the apparatus, and it was in early 1898 that Edison came up with his “Edison Standard Phonograph”. In the period between 1880 and 1910, the phonograph became so popular that it evolved to a widely mass commercialized consumer product. The “Standard” was the strongest selling type of Edison’s phonograph line. It counted as the entry model of cylinder players among the public. This could be due to the affordable price, which had – significantly - diminished to 20 Dollars (from its early days of 150 dollars) and the good quality this device was able to offer at the time. It was seen as a durable machine. The specificity with this particular model was the so called “standardization” of the cylinders, meaning that there was a standardized format that allowed the use of different cylinders on the whole line of the Edison Phonograph. This brought a greater compatibility and interchangeability between the different Edison phonograph models. Thus, the “Edison Standard” phonograph was the specific model that proved to become the top seller, and as over the course of the following years people developed different tastes, new models of the “Edison Standard Phonograph” were presented to the public as well. Thus, one author , passionate of the ”Standard” model, has determined the entire series of various models of the “Edison Standard Phonograph”. All begun indeed with the Standard Model “A” which seems to have been introduced in February 1898.

THE CYLINDER

While Edison had first used tin foil cylinders (therefore called “Tin Foil Phonograph” first) to engrave the waves of the sound mechanically thereon, from 1887 onwards, he improved considerably the phonograph by introducing the use of wax-coated cardboard cylinders. The tin-foil cylinder allowed to record sound and play it back, but the quality of the sound was bad, as it resulted in an unclean reproduction afflicted with strong background noise. Therefore, Edison didn’t manage to commercialize his phonograph in a fruitful manner . The efforts then developed to commercializing the phonograph as dictating machine wasn’t successful either, so that Edison now turned to developing a home entertainment talking machine . This activity went well, Edison also having created a new firm, the “National Phonograph Company” to commercialize his product, which happened at a lower price. The reason of this success had been that Edison had recognized at the right moment the popularity of the coin-operated phonographs in public places .

The improvement based on wax-coating had been developed by the two inventors Chichester Alexander Bell and Charles Summer Tainter who benefited from the invention of the phonograph to create its improvement, the “graphophone”. In 1889, wax cylinders became commercially available, marking a breakthrough in the history of recorded sound. Wax cylinders didn’t just improve the quality of the sound, but they also improved the durability of the cylinders. A wax cylinder is an around 10 cm long tube with a diameter of about 4 cm. During recording a cutting stylus cuts a groove that winds around the exterior of the cylinder. Each cylinder could record sound during up to two minutes. These cylinders could easily be removed and replaced on the mandrel of the machine which played them. And the cylinders could be shared. However, the number of times you could play it was limited, and while first wax cylinders were softer and could be played only 20 times, the composition of the wax was improved progressively so that the wax coating on the cylinders became harder and allowed them later on to be played 100 times. After Edison had rejected an offer of cooperation from Bell and Tainter regarding the further development of the phonograph, he began to further develop his phonograph and adopted Bell and Tainter’s idea of using wax as a recording medium. His main focus was on improving the copying process and the manufacturing process. Initially, the cylinders intended for sale were recorded directly by the various artists by positioning several speaking machines next to each other and starting the sound carriers for the recording at the same time. This individual procedure led to considerable costs, so that Edison soon began to look for methods that would replace this procedure. It is true that duplicating machines already existed with which a larger number of reels could be duplicated, in that a recorded reel rotated at the same rotational speed as the empty reel that was still to be recorded and the sound waves were transmitted by means of a lever system. However, these devices have not been able to meet the increasing demand for sound recording. Edison, therefore, after many attempts, devised a method for duplication in 1902, which is partly used in today’s production of records, the electroplating of the main sound carrier. For this purpose, a master was placed in a vacuum chamber between two gold leaf electrodes to which a high voltage was applied. The resulting arc tore off the finest pieces of gold from the electrodes, which settled and adhered to the roller rotating at a constant speed. As a result, a fine coating of gold was created, which, now electrically conductive, could be subjected to further galvanic processing. The wax original was removed and the remaining matrix, set in a brass tube, was immersed in liquid wax. If you then pulled the matrix out of the wax again, depending on the temperature difference between the matrix and the wax, a layer of wax of varying strength and controllable in thickness was deposited on the metal. The die itself was easily detached from the roll copy due to the different expansion coefficients of metal and wax. These sound carriers, known as chilled cast rolls or gold cast rolls, could now be sold in a suitable form.

USES OF THE PHONOGRAPH

Thomas Edison extensively reflected on the future use of the phonograph in an article he published in The North American Review in 1878 under the title “The Phonograph and its Future” . Edison’s initial idea about the use of the phonograph was not about music and entertainment. His idea was actually to have the phonograph used for a variety of purposes which were focused on language. Thus, he saw “letter-writing and other forms of dictation, books, education, reader, music, family record” as well suited to allow an efficient use of the phonograph. The advantage of the phonograph’s use in relation to, for example, letter-writing, was that it allowed in particular to be dispensed from having recourse to a stenographer. One can say that to a certain extent Edison’s initial idea was thus that of the device that was much later the “dictaphone” . In this respect reference should be made to an interesting example of how Edison conceived the use of his phonograph in offices where the secretary would not have to play the role of a stenograph but of the person transcribing on paper the spoken word previously recorded on the cylinder. Thus, an interesting video clip from 1910 can be viewed (see link in footnote ) which tells the story of the phonograph as the “The stenographer’s friend, or, What was accomplished by an Edison business phonograph” featuring a stenographer on a busy day at the office, where she is exhausted by the requests from her two bosses to stenograph their dictation, but doesn’t manage, with finally a person coming into the office and amused by the office’s problems as it doesn’t use the phonograph yet. At the end, they will get the phonograph and harmony and effective work comes back to the office, thanks to the Edison phonograph. While the video clip is a silent movie, it conveys the narrative in a very convincing manner, and in one of the title cards the main idea is expressed, saying “Transcribing the dictation. The pleasant task of doubling results”.

As is mentioned by one author , of the many uses of the phonograph that Edison envisaged, there was one “that still has no modern equivalent: the recording of the last word of the dying man. Beyond its obvious role as a family record, which Edison stressed, this rather morbid fascination may seem bewildering, but it has to be borne in mind that Edison was eager to present his invention as being an infallible scribe and unimpeachable witness. He thought that if it were possible to record the dying man’s last testament, this would be the most complete and efficient use of the phonograph to store sound over time. The recorded voice would carry the same authority as the written signature” , in Edison’s view.

However, with the spoken word fixed on the cylinder, one other specific idea of Edison’s was that of spoken books, which will “speak to blind people without effort on their part” . One can only be full of admiration considering the modernity and visionary thinking of Edison with respect to his invention. Indeed, the vinyl record will much later, in the second half of the 20th century, allow to commercialize spoken books on a larger scale, but one can say that Edison was prophetic in recognizing already in 1878 the interest which people would have in books spoken on a record : we know how important the sale of audiobooks, parallelly to the paper book, has become nowadays for the book trade, in particular literature, and creating an entire industry with famous actors reading the books on the record. It is thus interesting to note that Edison, when first speaking on his phonograph in 1877 (as mentioned above), did this by reciting a poem, the poem “Mary had a little lamb”, thus anticipating the literature audiobooks of today. In the same vein it is possible to refer to the podcasts which have known a huge development over the last 10 years and exist since the beginning of the century, though of course it is the internet and the easiness to download podcasts as well as spoken books at a very high speed which is an important reason for these recordings to have become so successful. Other uses which Edison attached to his phonograph were the teaching of elocution, the preservation of languages by exact reproduction of the manner of pronouncing, and other possibilities, which are all well-known today. However, while of course imagined by Thomas Edison at the beginning around the idea of a dictating machine, the phonograph progressively also proved to be a popular form of entertainment .

The End

In 1908 Edison changed the wax cylinder format by doubling the groove density. The usual playing time by cylinders was extended to four minutes and were advertised under the name “Amberol“. From 1912, Edison discontinued the production of two-minute cylinders and manufactured four-minute cylinders made of celluloid under the name “Blue Amberol Records”. But in the meantime, the discs had steadily grown in popularity and dominated the recording market. In the fall of 1929, Edison had to abandon all phonogram production as a result of the world economic crisis, thus ending the era of the phonograph as an entertainment device. However, dictation phonographs remained on the market in the U.S. for office use until the 1950s.

Source material

A band records a wax cylinder. The Red Hook Ramblers recording a wax cylinder at The Edison National Historic site. - YouTube A brief guide to Edison Standard Phonographs

https://www.tnt-audio.com/vintage/edison_cylinders2_e.html

History of the cylinder phonograph History of Edison Sound Recordings | Articles and Essays | Inventing Entertainment: The Early Motion Pictures and Sound Recordings of the Edison Companies | Digital Collections | Library of Congress (loc.gov)

Demonstration video of recording on a historic 1903 Edison Standard Phonograph https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wRTgl0qx6wE&pp=ygUhdGhvbWFzIGVkaXNvbiBzdGFuZGFyZCBwaG9ub2dyYXBo

Edison’s first recording with his new invention. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/63/Thomas_Edison_Mary_had_lamb.ogg

Edison T. A. (1903) Edison Phonographs. The Phonograph. An introduction. National Phonograph Company, Orange N.J. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/50073340e4b077c0b1bd2e53/t/559ac694e4b04ab9f76a05af/1436206740490/Edison_Phonographs_1903_Catalog.pdf

Exhibit of Edison Phonograph. (1888). Scientific American, 58(21), 328–328. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26095550

Kauper, Martin. Spotter’s Guide to the Edison Standard Phonograph https://apsblobdeve.blob.core.windows.net/article-pdf/Article_Intro_Edison-Standard.pdf

THE PHONOGRAPH. 1877 thru 1896. In “Scientific American” July 25, 1896. https://web.archive.org/web/20091202084044/http://www.machine-history.com/The%20Phonograph.%201877%20thru%201896

| The stenographer’s friend, or, What was accomplished by an Edison business phonograph | Library of Congress (loc.gov) Thomas A. Edison, Inc - Edison Collection (Library of Congress), Date 1910-01-01 |

Tewksbury, G. E. (1897). A complete Manuel of the Edison Phonograph. G. L. Frow, 92p.

Video where the functioning of the Edison phonograph is explained.

Bibliography

Butler, R.P. (2012). Thomas Edison Speculates on the Uses of the Phonograph. TECHTRENDS TECH TRENDS56, 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-012-0579-z

Camlot, J. (2003). Early Talking Books: Spoken Recordings and Recitation Anthologies, 1880-1920. Book History, 6, 147–173. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30227346

Darrell, R. D. (1933). Mr. Edison’s Phonograph: A Post-Mortem. The Sewanee Review, 41(1), 91–103. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27534846

DeGraaf, L. (1995). Confronting the Mass Market: Thomas Edison and the Entertainment Phonograph. Business and Economic History, 24(1), 88–96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23703274

DEVINE, K. (2013). Imperfect sound forever: loudness wars, listening formations and the history of sound reproduction. Popular Music, 32(2), 159–176. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24736755

Edison, T. A. (1878). The Phonograph and Its Future. The North American Review, 126(262), 527–536. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25110210

Read, O. (1949). The recording ad reproduction of sound. H.W. Sams. 364p.

Rehding, A. (2005). Wax Cylinder Revolutions. The Musical Quarterly, 88(1), 123–160. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3601015

Thompson, E. Machines, Music, and the Quest for Fidelity: Marketing the Edison Phonograph in America, 1877-1925. The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 79, No. 1 (Spring, 1995), pp. 131-171. Oxford University Press. 134p.

Webster, P. (2002). Historical Perspectives on Technology and Music. Music Educators Journal, 89(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/3399883